Have you ever thought about how many little steps go into things you do every day? This morning I brushed my teeth, braided my hair, and made coffee. The amount of smaller steps that go into each of those tasks is astounding. If I had written down every single action I took to brush my teeth or braid my hair, I would have written a task analysis for myself that I could then use to teach someone else how to brush their teeth or braid their hair. For kids on the autism spectrum who may have difficulties with processing or executive function, tasks that seem simple to us like brushing teeth can be overwhelming. Breaking those tasks down into component steps, much like you might make a to-do list for a multi-part project, can be a huge help for kids struggling with both social and non-social situations.

|

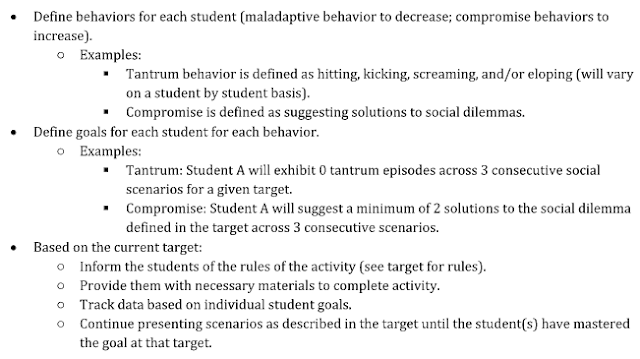

| Part of an example of task analysis for tooth brushing. As you can see, it breaks brushing teeth down into tiny, manageable parts |

A task analysis breaks a complex task like brushing teeth or greeting a peer down into its most basic steps. Task analyses are completed because there are a variety of steps that go into completing a complex task, and to teach that task you need to know that your learner can complete each step. Additionally, some tasks need to be completed in order; for example, brushing your teeth with a dry toothbrush then squeezing toothpaste onto that toothbrush doesn’t work. This is also valuable because you can reinforce each step as you teach it in a process called chaining, which can be done forward or backward. In forward chaining, you start by teaching the first of the steps you wrote down in your task analysis. This can be useful if your learner already has some or most of the requisite skills needed to complete the task. For instance, if tying shoes is your task and your learner can already put their feet in the shoes and grab the shoelaces, forward chaining might be the way to go. Backward chaining starts by teaching and reinforcing the very last step of a task, then the penultimate step, and so on. This can be good because you’re always reinforcing the final outcome of the task, so no matter what step you’re currently teaching, your learner is always completing the task independently. Breaking down your task and teaching through chaining allows for greater access to reinforcement throughout the teaching process, which can be especially useful in social situations, For more information on reinforcement in social situations, look out for our upcoming post. The degree to which you simplify the steps depends on your learner. For example, if the task is “washing hands” some learners will need “turn on water, put on soap, scrub, turn off water,” while others will need a more detailed list. Sometimes pictures can also be helpful in teaching each step, like adding a picture of your learner’s toothbrush and faucet handle to their list of steps. Knowing what will be most helpful to your learner is crucial to making a useful task analysis.

Task

analyses can also be completed for social skills group. First, a social skills

assessment needs to be done. Things like ABLLS and VBMAPP as administered by a

professional behavior analyst can be used to assess the learner’s social skills.

Once you’ve selected a goal, then you can break it down. For example, we find

that during issues of dispute, one of our learners typically tantrums rather

than selecting a compromise for a solution. Now we have our goal and it’s time

to break it down. Refer back to the hand washing example-the component steps

will be based on the learner’s needs. An example of component steps for

compromise would be identifying functional compromise solutions when presented

with a social dilemma with a peer. In order to identify those solutions and

break that process down into steps, keep in your learner’s goals and program

targets. For more information on setting goals for social group, refer back to

our blog post here. One example of a situation where a social task analysis for

compromise might be useful might be a social skills group science project. All

of the learners in the group need to compromise on the topic of the science

project, which means no one is going to get to do exactly what they want to do.

Luckily, since this hypothetical science project takes place in a social skills

group, each kid can have a task analysis done for compromise with adults

helping to facilitate the interactions and prompt the different steps of the

task analysis. Once the learners have practiced using their task analysis during

a contrived situation like social skills group, they can generalize to natural

situations like hanging out with friends or working on a project in class,

fading out adult prompting to boost independent social interactions.

Task

analysis is important because while some tasks might seem second nature to

neurotypical people, they can be daunting for people on the autism spectrum.

Interacting with other people, even before morning coffee, is simple for

neurotypical people because we know the various steps that apply to each social

situation, and it can be difficult to try to explain those steps to someone

else. Task analyses break these social situations down into the steps we

already go through and make them accessible to people on the autism spectrum

instead of just expecting them to do the things their typical peers do. We all

make task analyses for ourselves, we just usually call them to-do lists or have

tasks mentally broken down in our heads. Task analyses are just versions of

these lists, modified to best help our learners navigate the world.